Marines cw-1 Read online

Page 12

Solid is a bit of an overstatement - the first thing they brought me looked like soupy oatmeal that had been through a food processor, but I could have waxed poetic about it for hours. Any food that entered my body through my mouth and not directly into my bloodstream was A OK with me.

I was strapped into a machine with my torso disappearing into a shiny metal cylinder that extended to just under my sternum. Below the cylinder each stump extended into its own clear plastic tube that would hold and support the new leg as it grew. Inside the cylinder, in addition to the machinery that powered the regeneration, was an assortment of plumbing that attended to by bodily functions while I was strapped in, immobile for weeks.

I was most concerned with - in order - pain, boredom, and going a little crazy because I could hardly move, but I have to admit it was a learning experience watching my legs grow. At first it was just the bone, growing down from the existing stump at a rate of about 6 centimeters a day. I used to stare at it to see if I could perceive it actually growing. I thought maybe I could a couple times, but I was never sure.

The whole process was monitored and controlled by the medical computer. I was growing legs from my own genetic material, but I needed adult legs, not the baby legs I was born with that grew over 15 or 20 years. Organs were regenerated in almost the exact way they initially formed and grown to adult size, albeit at a greatly accelerated rate. A new liver, for example, would start as a tiny one that would grow, much as it does in a fetus and later a child as it ages.

But my new legs were grafting right onto my adult body. The doctors couldn't grow tiny fetus legs and allow them to gradually increase in size. The genetic material had to be stimulated to grow in a certain way directly on my body, and this was manipulated by medical lasers, electrical pulses, and a variety of other tools.

Once my new tibias and fibulas were finished with their development, I was amazed at the spectacle of my new skeletal feet growing. About the same time my upper legs began to grow muscles, cartilage, nerves, arteries, and the rest of the slimy stuff inside all of us. For a while I was a live anatomy lesson - upper leg showing the muscular system and lower leg the skeletal.

I mentioned that all of this hurt, didn't I? I'd describe what new nerves feel like when they are growing, but honestly, I just don't know how to put it into words. It hurts. A lot.

Doctor Sarah would visit me as often as we could, and we'd talk about different things. Of course, I had realized early on that Doctor Sarah was also Captain Sarah, and that she was every bit as much a marine as I was, and outranked me to boot.

It also meant that, as angelic and patrician as she looked, she probably had not had the easiest life before the Corps. Most of us were plucked from one gutter or another. But I didn't ask, and she didn't ask me either. Since the majority of us had shitty backgrounds, it was traditional to keep it off limits. We were all reborn into the Corps, our old sins expunged.

We were both from New York, and had both lived in the MPZ when we were young, but that's as far into that subject as we got. She received her medical training in the Corps, and before that she made a few assaults, though not as many as I had. She asked me about Achilles, about what it had been like on the ground. She'd served on one of the support ships as surgeon, but never made it to the surface. With a little help from Florence, she got me through the boredom and pain and frustration. I think helping me helped her a little too. The war had not been going well, and I can only imagine how neck deep in blood and partial soldiers she'd been every day.

Once the skin had completed its growth my regeneration was declared complete. That doesn't mean I was as good as new though. In theory, my new limbs were exact copies of my old ones, though the reality was a bit more complicated. I hadn't spent a couple years learning to walk with my new legs, and the neural pathways required to move them were slightly different. It took a month of hard physical therapy before I could walk around normally, and longer before I felt really comfortable with my balance. You'd be amazed at the sweat you can work up holding onto parallel bars and willing your new legs to move a few inches.

Once I was up and walking around, it was time for general physical rehab. I was now healthy, more or less, but I certainly wasn't the toned and fit combat soldier I had been. I was 20 kilos lighter than before I was wounded, and it was mostly muscle that was gone. So they put me on an aggressive training regimen, and most wonderfully of all, they finally started feeding me real solid food consistently. I'd worked my way through the mushy cereals and clear soups, and I can't even express how good a sandwich tastes after weeks of slop.

The training was hard and exhausting, but it was a true pleasure. I got outside, breathed the fresh air, felt the sun (suns, actually) on my face. I started taking short walks, but before long I was running half marathons every day. There was a pristine lake on the hospital grounds, and I took a daily swim too. The air, the water, the sun - it all made me feel alive again, a little more each day.

I spent afternoons in the training rooms, going through one strength-building routine after another. As my strength and endurance increased I really began to feel like myself again. I'd been weak and infirm for most of a year, and now I felt as if I'd been truly reborn.

The care I received was amazing, and I have nothing but praise and gratitude for my entire medical team. Doctor Sarah, of course, but also the other surgeons and all the tech and support personnel. I knew the marines took care of their own, but it was incredible to see how much effort was expended on a single wounded sergeant. Back on Earth, only a member of the Political Class would get this kind of treatment, and it would have to be a highly placed member at that.

When they finally declared me healthy and discharged me, I made point of thanking each of my doctors and medtechs before I left. They'd literally given me my life back. It was pretty emotional saying goodbye, but when I got to Doctor Sarah it just then struck me that I wasn't going to be seeing her every day anymore. I would actually see her again many times, but I didn't know that then. She hugged me and tearfully reminded me she had promised I'd be good as new. One of the techs took an image of us and flashed it to our data units. So I took my duffel bag and my picture of Doctor Sarah and me, and I walked out of the hospital into the dazzling sunlight. Both of Armstrong's binary stars were high in the morning sky, and it was as magnificent a day as I have ever seen on any planet.

I took the monorail to the spaceport and boarded the shuttle to Armstrong Orbital. Before I even checked into my billet I reported to the armorer to be fitted for a new suit. My old armor was almost torn to shreds saving my life, but I'd have needed a new set anyway. I looked the same as I did before, but with all the weight I lost and then gained back, not to mention growing new legs, I would have needed new armor. A fighting suit had to fit you like a glove to function properly.

I had 60 days of leave for rest and recreation, but I really wasn't interested. I'd had all the rest I could take in the hospital, and I was anxious to get back into the fight. Plus, I had a bad case of missing my doctor, and I figured hitting ground on some planet or another was the best way to put it out of my mind.

There was a problem with that theory, however. It turned out I wasn't going right back to the battle after all. While I was in the hospital I found out that the colonel had not only nominated me for a decoration; he'd also recommended me for officer training. The day after I was discharged I got the orders. I was on my way to the Academy. The next time I was bolted into a lander it would be as Lieutenant Cain.

Chapter Seven

The Academy Wolf 359 III

Humanity occupied, to some extent or another, 285 planets and moons located in about 700 explored solar systems. Some of these were fairly robust colonies, generally small but growing rapidly. Others were just remote outposts, usually placed to exploit some valuable resource or to operate a refueling station for ships travelling between systems. A few were core worlds, the first colonies established, which had now grown into sizable populations

and modest industry.

The warp gates that connected them were naturally occurring gravitational phenomenon that physicists had yet to fully explain. Some solar systems had only one; the largest number yet discovered was ten. A system with three or more was particularly valuable. It was the kind of place we'd likely be found, there to hold onto it or to take it away from someone else.

I had been surprised at how much classroom education there was in marine basic training. But that was nothing compared to the Academy. The powers that be had obviously decided that to become an officer one must have a head full of obscure knowledge of dubious utility. Or something along those lines. There was math, science, engineering and, of course, battle tactics. A lot of it was boring but relatively easy, and I didn't have to pay too much attention to get through it. The one thing I really enjoyed was the history. And we got a lot of it. Real history, not the manufactured drivel taught in public schools back home.

Our world was the product of the Unification Wars, a series of bitter conflicts lasting 80 years that finally ended with the familiar eight superpowers controlling the globe. The root causes of the wars were many, though so many records were lost over decades of desperate fighting it is only possible to speculate on the relative importance of each.

By the mid-21st century the democracies of the west, which had been the drivers of 20th century growth, were in rapid decline. Beset with corrupt and bloated governments, bankrupt by decades of appalling mismanagement, and unable to recapture the economic dynamism of their past, they were teetering on the verge of collapse.

The developing nations of the world, while they enjoyed rapidly-growing economies built largely on cheap labor, proved to be somewhat of an illusion of prosperity. Government interference, fraudulent reporting, and a lack of economic flexibility caused the growth to falter, and when the world economy started to crumble, one by one they fell into turmoil and revolution.

There was unrest in Asia, in Latin America, even in Europe. But the Wars started in the Mideast. The Middle East, which had risen to power and wealth by exploiting massive reserves of fossil fuels, was thrown into chaos by the development, in 2048, of commercially feasible fusion power. Within a decade, demand for petroleum had declined 75%, and the price of a barrel of oil dropped from a high of $500 to less than $30.

An astonishingly small portion of a century's oil riches had been invested in anything productive, and within a few years there was mass starvation, rioting, and rebellion throughout the region. Unrest led to riots, which in turn led to open revolt. Warfare erupted in a dozen places at once as despotic regimes clung desperately to power while their starving citizens stormed the barricades.

The nations of the west, no longer wealthy enough to provide substantive aid nor powerful enough to impose their will worldwide, were unable to stem to flow of global unrest, and revolt spread across the globe. Terrorism became a worldwide scourge, culminating in several nuclear incidents that killed millions.

Teetering governments facing rebellion responded with brutal force; those of more stable nations resorted to ever stricter internal security measures until they controlled virtually every aspect of their citizens' lives. Democracy, such that it once was, disappeared from the face of the Earth. The forms were still followed, yes, but the substance of republican government was freely surrendered in the end by scared populations willing to trade any freedom for increasingly unreliable promises of security.

In 2062 the First Unification War erupted not far from the Mesopotamian basin where civilization began, and for the next three-quarters of a century combat raged in every corner of the globe. By the time the wars were over almost 80 years later, 75% of the world's population had perished, and there were only eight nations left on Earth. The superpowers.

They were bankrupt, exhausted, and devastated. Their economies were ravaged, their armies depleted. Finally, when there were no resources remaining to sustain world war, the Treaty of Paris ended the fighting. On Earth.

Barred from terrestrial warfare by a treaty they were too afraid to violate, the exhausted superpowers took their rivalries into space. Earth was prostrate, drained of resources, scarred by nuclear exchanges, and in desperate need of the wealth that could be exploited from distant worlds and asteroids now that the discovery of the warp gate had opened the universe to exploration.

Space is limitless, so at first the Powers explored peacefully, assuming that there was plenty of room for everyone. But the warp gates that allowed speedy interstellar travel were not infinite, and it soon became apparent that some systems were of great strategic value because of their locations and where their gates led. Choke points developed, and before long the Powers were at war again, this time in space.

The Treaty of Paris has been scrupulously obeyed, as all of the governments realize that the next war on Earth will likely be the last. Armies in space, though staggeringly expensive, are small in scale compared to the massive legions mobilized during Earthbound world wars. Our battles are every bit as violent, bloody, and deadly as any ever fought, but the lands we waste are sparsely populated frontier worlds and not cities with populations in the millions.

We were fighting the Third Frontier War, and all of human-occupied space was on fire. The periods between named, declared wars also saw their share of raids and battles, but these were generally intermittent and fought at a much lower intensity level. The Second Frontier War had lasted 15 years, and though not entirely conclusive it had been a marginal victory for the Alliance and its allies. The interwar skirmishes occurring afterward had swung a bit the other way, and our position had weakened, a trend that accelerated during the first few years of declared war.

Depending on the current status of its ongoing struggle with the Caliphate, the Western Alliance had either the largest or the second largest empire of colony worlds. The Central Asian Combine was a close third, and the Pacific Rim Coalition a distant fourth.

Since the Caliphate and the CAC were usually allied against us, we had our hands full, and we were constantly wooing one or more of the other Powers to side with us. Even when we were allied with the PRC we were still outnumbered, and our network of warp gate pathways was exposed and vulnerable to interdiction.

The other Powers were less of a factor in space, though all of them had some network of colonies, and the alliances between them shifted as goals and expediencies changed. The Russian-Indian Confederation was weak in space, but usually allied with us. The Central European League and Europa Federalis were mostly concerned with fighting each other, and would ally with the stronger powers as it suited their purposes. Since an alliance with one usually meant war with the other, it was more or less a zero sum game.

The South American Empire had a tiny group of colonies, but they were clustered together and highly defensible. The Empire rarely aligned with anyone in the major wars, preferring an opportunistic neutrality. Their forces frequently served as mercenaries for the other Powers, and they would often fight on both sides at different times in a conflict - sometimes even at the same time.

Though there were only eight superpowers on Earth, there were nine in space. The Martian Confederation was formed when the early colonists of the red planet broke away from their terrestrial parent nations during the later stages of the Unification Wars and banded together to form a loose union. The Confederation controlled the largest group of developed colonies in Earth's solar system and a small collection of interstellar settlements as well. While only a fraction the size of the other Powers in population, the Confederation had the most advanced technology of any of the Superpowers, and its forces, while small, were well-trained and equipped. Mars tended toward neutrality, but when the opportunity presented itself they were a welcome ally.

All of the Earth governments were authoritarian to some extent or another; only the Martian Confederation was a real republic. The Alliance national bodies - the U.S., the U.K., Oceania, and Greater Canada - outwardly retained republican forms, but they were reall

y oligarchies run by entrenched political classes. Office holders had to be graduates of the Political Academies, and the politicians controlled who was admitted, creating an almost hereditary class system. The occasional outsider could work his way into the upper classes, but such an individual would require the sponsorship and patronage of someone already powerful.

The middle classes, mostly educated professionals of one sort or another, lived a fairly spartan, but moderately comfortable, existence much like my parents had. Few made any trouble because they were terrified of losing their position and falling into the underclass, again as my parents had. It was a system that worked, at least after a fashion and, if innovation, creativity, and freedom were not what they once had been at least civilization survived. It almost hadn't.

For most people a tiny apartment in an area protected from the worst crime, an adequate supply of rations, and cheap entertainment was enough. For those who wanted more there was space. The colonies of most of the Powers enticed those who craved more freedom, those who were driven to create and build. The new worlds attracted many of Earth's best and brightest, and these fledgling societies, so much smaller than the terrestrial nations, tended to be significantly more democratic than the home governments. They were each a part of their Superpower of course, and they relied upon the parent to provide protection and support. But as long as the stream of vital resources flowed back to Earth, the colonial governments were pretty much allowed to do as they pleased.

Most of us in the military were castoffs from Earth society in one way or another. The Corps looked for recruits with a strong independent streak, something that was not conducive to success in the mainstream world. We weren't the mindless robots in serried ranks of armies past. A modern soldier, operating 20 meters from his closest comrade and 20 light years from the chain of command, had to be innovative and ready to take the initiative.

The Emperor's Fist

The Emperor's Fist Blood on the Stars Collection 1

Blood on the Stars Collection 1 Attack Plan Alpha (Blood on the Stars Book 16)

Attack Plan Alpha (Blood on the Stars Book 16) BOB's Bar (Tales From The Multiverse Book 2)

BOB's Bar (Tales From The Multiverse Book 2) The Others

The Others Nightfall

Nightfall Empire's Ashes (Blood on the Stars Book 15)

Empire's Ashes (Blood on the Stars Book 15) Wings of Pegasus

Wings of Pegasus Crusade of Vengeance

Crusade of Vengeance The Last Stand

The Last Stand Blackhawk: Far Stars Legends I

Blackhawk: Far Stars Legends I Call to Arms: Blood on the Stars II

Call to Arms: Blood on the Stars II Cauldron of Fire (Blood on the Stars Book 5)

Cauldron of Fire (Blood on the Stars Book 5) Revenge of the Ancients: Crimson Worlds Refugees III

Revenge of the Ancients: Crimson Worlds Refugees III Crimson Worlds Successors: The Complete Trilogy

Crimson Worlds Successors: The Complete Trilogy The Grand Alliance

The Grand Alliance Portal Wars 1: Gehenna Dawn

Portal Wars 1: Gehenna Dawn MERCS: Crimson Worlds Successors

MERCS: Crimson Worlds Successors Crimson Worlds: 08 - Even Legends Die

Crimson Worlds: 08 - Even Legends Die Winds of Vengeance

Winds of Vengeance Invasion (Blood on the Stars Book 9)

Invasion (Blood on the Stars Book 9) A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds III)

A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds III) Marines

Marines Black Dawn (Blood on the Stars Book 8)

Black Dawn (Blood on the Stars Book 8) Shadow of Empire

Shadow of Empire Galactic Frontiers: A Collection of Space Opera and Military Science Fiction Stories

Galactic Frontiers: A Collection of Space Opera and Military Science Fiction Stories Winds of Vengeance (Crimson Worlds Refugees Book 4)

Winds of Vengeance (Crimson Worlds Refugees Book 4) Dauntless (Blood on the Stars Book 6)

Dauntless (Blood on the Stars Book 6) Portal Wars: The Trilogy

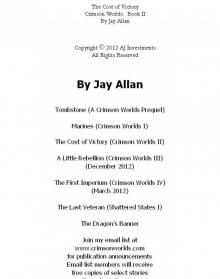

Portal Wars: The Trilogy Marines cw-1

Marines cw-1 The Cost of Victory

The Cost of Victory Marines (Crimson Worlds)

Marines (Crimson Worlds) The Ten Thousand: Portal Wars II

The Ten Thousand: Portal Wars II The White Fleet (Blood on the Stars Book 7)

The White Fleet (Blood on the Stars Book 7) Crimson Worlds Collection III

Crimson Worlds Collection III The Black Flag (Crimson Worlds Successors Book 3)

The Black Flag (Crimson Worlds Successors Book 3) Tombstone

Tombstone Gehenna Dawn

Gehenna Dawn A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds)

A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds) Ruins of Empire: Blood on the Stars III

Ruins of Empire: Blood on the Stars III Dauntless

Dauntless Shadows of the Gods: Crimson Worlds Refugees II

Shadows of the Gods: Crimson Worlds Refugees II The Dragon's Banner

The Dragon's Banner Echoes of Glory (Blood on the Stars Book 4)

Echoes of Glory (Blood on the Stars Book 4) Crimson Worlds: 04 - The First Imperium

Crimson Worlds: 04 - The First Imperium The Prisoner of Eldaron: Crimson Worlds Successors II

The Prisoner of Eldaron: Crimson Worlds Successors II The Cost of Victory (Crimson Worlds)

The Cost of Victory (Crimson Worlds) Duel in the Dark: Blood on the Stars I

Duel in the Dark: Blood on the Stars I Into the Darkness: Crimson Worlds Refugees I

Into the Darkness: Crimson Worlds Refugees I Crimson Worlds Refugees: The First Trilogy

Crimson Worlds Refugees: The First Trilogy The Cost of Victory cw-2

The Cost of Victory cw-2 Stars & Empire 2: 10 More Galactic Tales (Stars & Empire Box Set Collection)

Stars & Empire 2: 10 More Galactic Tales (Stars & Empire Box Set Collection) Flames of Rebellion

Flames of Rebellion Stars & Empire: 10 Galactic Tales

Stars & Empire: 10 Galactic Tales The First Imperium cw-4

The First Imperium cw-4 Crimson Worlds: 07 - The Shadow Legions

Crimson Worlds: 07 - The Shadow Legions Storm of Vengeance

Storm of Vengeance Crimson Worlds Collection I

Crimson Worlds Collection I Rebellion's Fury

Rebellion's Fury Homefront: Portal Wars III

Homefront: Portal Wars III Tombstone (crimson worlds)

Tombstone (crimson worlds) Crimson Worlds: Prequel - Bitter Glory

Crimson Worlds: Prequel - Bitter Glory Crimson Worlds: Prequel - The Gates of Hell

Crimson Worlds: Prequel - The Gates of Hell The Fall: Crimson Worlds IX

The Fall: Crimson Worlds IX Crimson Worlds: War Stories: 3 Crimson Worlds Prequel Novellas

Crimson Worlds: War Stories: 3 Crimson Worlds Prequel Novellas Enemy in the Dark

Enemy in the Dark Crimson Worlds Collection II

Crimson Worlds Collection II