Crimson Worlds Collection I Read online

Page 9

The ground was torn up even worse than it had been a couple days before, and even in armor we lost time as we scrambled in and out of craters filled with neck-deep water and muck. The strength amplification of the armor let you power your way through the mud, but it didn't stop you from sinking in with every step.

Twice I had to halt the group so we could turn and engage enemy militia who had caught up to firing range. Both times we hosed them down with heavy fire and they broke and ran. It didn't cost us much time, but every minute counted. I knew those deadlines were real. If the fleet was really in danger they weren't going to risk it to pick up the shattered remnants of a strikeforce. It was brutal mathematics - marines were cheaper and easier to replace than battleships. They'd stay as long as they could...and not a minute longer.

I was surprised that we'd managed to retreat back to the staging area without losing anyone. I'd been waiting for the enemy to hit us hard. If they'd have launched a major attack while we were all retreating, none of us would have gotten off-planet. But the truth is we had just about won the land battle when the recall orders came. The enemy wasn't hitting us while we retreated because they didn't have anything left to hit us with. For all the missteps and enormously heavy casualties, Achilles was failing because we couldn't hold the space above the planet, not because we couldn't take the ground.

The rally area was a confused mess, with units straggling in from all directions and being loaded on whatever ship was available. Our group got hustled onto a tank landing shuttle that launched a few minutes after the hatches slammed shut behind us.

It was a rough ride to orbit. The ship wasn't built to hold infantry, and we were just hanging on however we could. The hold was silent. We all knew what a disaster the operation had been, and while none of us knew exactly how this affected the overall war, we had a pretty good idea it was bad.

We were right. It was bad. But I don't think any of us realized just how bad.

Chapter Five

AS Gettysburg

En route to Eta Cassiopeiae system

I was one of the 14.72% of the ground troops in Operation Achilles to return unwounded.

Technically speaking, I didn't exactly return because the Guadalcanal wasn't as lucky as I was. She'd taken a hit to her power plant during the initial approach, and she was still undergoing emergency repairs when the withdraw order was issued. There was no way she could outrun the enemy fleet on partial power, so she offloaded all non-essential personnel and formed part of the delaying force, holding off the attackers long enough to evacuate most of the surviving ground forces.

The way I heard it, the old girl wrote quite a final chapter for herself, taking out two enemy cruisers and damaging a third before she got caught in converging salvoes and was blown apart by a dozen missile hits.

I'd been on the Guadalcanal for three years, and it was surreal to think that she was gone. Captain Beck, Flight Chief Johnson, even that short little tech who used to play cards with us...I can't even remember his name. All dead.

But those losses seemed distant, theoretical, not quite real. We had plenty of empty places right in our own family. My battalion had landed with 532 effectives. There were 74 of us now.

The major was dead. Lieutenant Calvin was the only officer still fit for duty, so he took command of the battalion, a promotion tempered by the fact that he commanded only 24 more troops than he did when he'd led his platoon down to the surface just over a week before.

Captain Fletcher was wounded. I'd been bumped to sergeant the day after we embarked, and I was in temporary command of the company...all 18 of us. Getting missed has always been a good way to advance through the ranks.

We were loaded onto the Gettysburg with various remnants of a dozen other units. It was a different world. The Guadalcanal had been a fast assault ship designed to carry a company of ground troops and their supplies. She'd carried about 60 naval personnel in addition to the 140 or so ground troops.

Gettysburg was a heavy invasion ship, carrying a full battalion along with a flight of atmospheric fighters, combat vehicles, and enough supplies for a sustained campaign. At least when fully loaded she did. Over a kilometer long, she was ten times the tonnage of the Guadalcanal.

But now she was carrying 198 troops, the remnants of 3 full assault battalions, along with a vastly depleted store of supplies and two surviving fighters - one hers and one from another carrier.

The fleet managed to escape with serious but not crippling losses, and once we were through the warp gate the massive assemblage started to break up, as assets were redeployed to meet various crises in different sectors.

And there were plenty of threats to deal with. We were on the run, and the enemy knew it. We'd stripped everything bare to mount Achilles, and now the enemy was trying to exploit our weakness.

It was obvious things were pretty bad, but we really knew the situation was desperate when we were rushed to the Eta Cassiopeiae system without any rest or even resupply. Eta Cassiopeiae was vital to us, a nexus with 5 warp gates, three leading to other crucial Alliance systems. Columbia, the second planet, was a key colony and base, and the moons of the fifth and sixth worlds were mineralogical treasure troves.

If they were rushing exhausted fragments of units there without refit, they were expecting the enemy to attack. Soon. So the troops got 48 hours to recover from the Slaughter Pen, while the 2 lieutenants and 6 sergeants available to command them worked out a provisional table of organization and discussed the best training regimen to get them fit for combat again in short order.

I ended up with 23 troops plus myself, divided into four normal fire teams and one three man group with a portable missile launcher, normally a company-level heavy weapon.

The ship was less than half full, so there was plenty of room in the gym and training facilities. We put everyone on double workout sessions, which caused a lot of grumbling. But it also kept everyone busy, without too much time to think - either about where we had been or where we were going.

Just like the Guadalcanal, the Gettysburg's training areas were near the exterior of the ship where the artificial gravity was close to Earth-normal. The deep interior of the vessel, which was close to a zero gravity environment, was dedicated to storage and vital systems.

A spaceship is far from roomy, even with half the normal number of troops present, so it was just as well to keep everyone busy whenever possible. Our expedited itinerary meant lots of extra time strapped into our acceleration couches with nothing to do but think and try to breath while you were being slowly crushed. So, when the troops were out of the couches, I was just as happy to have them working up a sweat as crawling off somewhere to brood on defeat.

Eta Cassiopeiae was three transits from Tau Ceti, and it took us about 6 weeks of maneuvering between warp gates before we emerged at our destination and another ten days to reach the inner system and enter orbit around Columbia.

Since we were reinforcing a world we already held, and not mounting an attack, we were spared the rough ride of a planetary assault. It was a good thing too, because there wasn't a single Gordon lander left on the Gettysburg. We ferried down in the two available shuttles, about 50 men at a time, landing at the spaceport just outside the capital city of Weston.

Columbia was a beautiful planet, mostly covered by one giant ocean and dotted with numerous small archipelagos. The single major continent, where 95% of the population lived, was a small oval chunk of ground just 500 kilometers north to south and less than 300 east to west. Situated in the temperate northern polar zone, its climate was almost perfect.

The small island chains, mostly located closer to the equatorial zone, were sparsely inhabited by a hardy breed of colonists who braved the intense heat to produce a variety of valuable products from the Columbian sea, including several useful drugs obtained from the native fish.

It was good to get off of a spaceship and have my feet touch the ground without someone shooting at me, a pleasure that was tempered by the

knowledge that while we weren't attacking, we were almost certainly a target.

All my battles to date had been offensive. We were an assault battalion - that's what we were trained for, and that's what we did. But circumstances had put us on the defensive, and now we would get a chance to dig in and fire missiles at the enemy landers - all those things that looked so good when we were attacking. But now we had a different perspective and sitting as a target and waiting for the enemy to hit us, when and where he chose, didn't seem so appealing either. We were used to having the initiative, and I'm not sure trading it for a foxhole or two was such a good deal.

We'd also be alone, totally cut off on this planet to hold it or die. When we attacked we always controlled local space, and if the battle went against us we could retreat back to the ships. Operation Achilles had been a disaster, but it still ended with almost half of the troops evac'd, even if two-thirds of those were wounded.

But the Gettysburg was heading out as soon as the landing was complete. The navy simply couldn't mount a credible defense of the system. Not now. So the strategy was to dump as much force as possible on the planet and try to hold out until a relief force could arrive.

We were milling about the field, wearing our armor because that was the easiest way to transport it down, but with visors up and weapons systems powered down. Whatever else an attack might be, it wouldn't be a surprise. The warp point probes and the spy satellites in planetary orbit would give us plenty of warning when the enemy was inbound.

I knew from the briefing we'd received on the Gettysburg that the garrison commander was Colonel Elias Holm, a veteran marine who was now fighting his second war. He'd already added two new decorations to the glittering array of medals he'd been awarded during the Second Frontier War. It occurred to me that there was a good chance we'd be helping him win his third. Holm was a high-powered commander for this posting, but he was just what was needed to take a bunch of broken, demoralized units and forge them into an iron defense.

One of the heroes of the Corps, Colonel Holm was the subject of a number of legends and rumors, and we all expected some two and a half meter giant who breathed fire and walked on water. But the man striding our way from the command building could have been any one of us. A bit older, yes, with a head of close-cropped, thinning brown hair, sprinkled with gray. He was a touch under two meters tall, with a lean, muscular build. There was a faint scar running from his hairline all the way down the right side of his otherwise pleasant but careworn face.

Any sense of disappointment that Hercules himself did not step forward to greet us vanished when he stopped walking and started to speak. Everything I learned about truly being a leader started that day. His voice was warm and friendly, but also firm and commanding. "Welcome to Columbia." The man exuded confidence with every word, and just listening to him was inspiring. "I know all of you were in Operation Achilles, and you all deserve a long stretch of R & R after that clusterfuck. But the fortunes of war are not often what we would like them to be, and as marines we do what we must. Always."

He paused and looked us over. He wasn't wearing armor, just a standard gray and black field uniform, which was clean and neatly pressed, adorned with nothing but a simple Colonel's eagle on each shoulder. His black boots were shiny and neatly polished, except around the bottom where they were crusted with reddish mud.

"You marines are all veterans. Even if Achilles was your first drop you've earned that distinction now. So I'm going to give you a good idea of what we're up against. With you and the forces the Pericles dropped off yesterday we've got 1,242 regular troops, about half of which are fully-armored marines. Most of rest of the frontline assault troops were at Tau Ceti like you, which means you're all under-supplied, and your command structures are shot to hell. We've also got 1,040 planetary militia who are well-trained and equipped. Columbia is a popular retirement spot, so the militia is well-leavened with marine vets. A lucky break. The militia also have 6 tanks...old Mark VI Pattons."

Ok, so we had about 2,300 troops. Probably more than I would have expected, especially considering how urgently they rushed less than 200 of us here. Of course everything depended on what they threw at us. This system was worth a considerable effort, but we just had no way of knowing what the enemy could bring to bear on us quickly or how hard they'd hit us from space before landing.

"We're going to get everyone billeted the best we can, and I'm going to try to give you Achilles people at least a little rest. I just don't know how long we have until we are attacked. It's possible we may not even be attacked," - yeah, sure - "but we will assume that we are a target. We are building defensive works around all the vital installations...trenches, strongpoints, and lots of underground bunkers and tunnels. A lot of that is already in place, and we're going to be working on the defense grid right up until the enemy starts landing."

So that "little rest" was going to be very little.

"We're going to man the positions with the militia and marine supporting units. All the powered infantry, plus the tanks, are going to be organized into four reaction forces. We're going to hide you underground in key spots and throw you at the enemy where you will do the most damage. You're going to be our ace in the hole, a mobile reserve that gives us the chance to surprise the attacker and take away some of his initiative."

A pretty daring strategy. The powered infantry was only a little over a quarter of our numbers, but we were well over half the overall strength and firepower. Pulling us all out of the fight at the start threatened to fatally weaken the defense, especially since the enemy would almost certainly be attacking with powered units themselves. But it gave us a real chance to win a decisive victory if things worked out. If the enemy fully committed to attacking the other units, we'd have one hell of a tactical surprise for them.

"All the Achilles people get the rest of the day to themselves. We'll get you billeted, and then I want you to grab some extra sack time. You're going to need it. Everyone's putting in 12 hours a day working on defenses - remember, a day here is 27.5 Earth hours - but you guys are going to do 8 with an extra 4 hours of rest. Starting tomorrow. Officers and sergeants, stow your suits and gear and report to the control center for a briefing in 30 minutes at 1300 hours."

About half a dozen non-coms had walked up behind him, and a burly sergeant began barking out instructions about getting us settled in. I told my senior corporal to see about the billeting, and I wandered over to where the rest of the unit commanders were already congregating.

A corporal led us to a maintenance shed where we were able to store our armor. I told the AI to pop my suit, and after asking me if I was sure (and I really hated having to repeat myself to a machine) it powered down the servo-mechanisms, and I could hear the latch-bolts sliding open.

The cool outside air felt great, and I climbed out, feeling as always a bit like a snail wiggling out of its shell. My kit was strapped to the back of my armor, and I opened it up and pulled out a uniform and boots. The room was full of naked marines doing the same thing. We got dressed, and our kits were moved to our billets while we headed over to the briefing dressed in wrinkled but clean gray field uniforms.

Mostly the colonel repeated what he had told us on the landing field, but we got a bit more detail. First, we got some hard intel. The enemy was definitely going to attack, and probably within the next two weeks. And it was going to be a significant force. We didn't have solid numbers, but it was a good bet we'd be hard-pressed to hold out.

Second, Colonel Holm had been far from idle. He'd had most of the civilians conscripted into labor battalions to help build defenses. The interlocking grid he had in mind was a lot closer to finished than I'd thought when he first mentioned it. Having just faced something very similar on Tau Ceti III, I wasn't about to underestimate the effectiveness of hardened defenses, especially under a commander like Holm.

Our supply situation wasn't ideal, particularly among the powered infantry units. Because our weapons had access to the energ

y generated by our suits, we were able to put out a lot of firepower. But this time we were low on ammunition, so we'd have to make our shots count. This was another reason why the colonel wanted to hold us as a surprise attack force. We'd be able to conserve ammo and use it when we could hit the hardest and make it count.

After the initial briefing we went into a question and answer session. The colonel asked for input and opinions, and then surprised me even more when he knew most of our names and could identify us by sight. This guy was one hell of a leader. Sometime in the last day or two he'd accessed the personnel files from the Gettysburg computer and committed to memory the face and name of just about every officer and non-com.

We spent the next two hours or so looking at maps, reviewing proposed deployments and going through a few scenarios for ways our units might exploit opportunities. This was the first time I'd ever been in on an overall battleplan, and it made an impression on me that Colonel Holm not only wanted to familiarize us with it, but he also asked for comments and input.

When we broke up I headed across the landing field to the billeting area. Our troops had been housed in what looked like a dormitory for workers. I had just about enough time to check on the troops before evening mess.

Everything checked out. The troops were all settled in. In fact, most of them had grabbed a couple hours sleep while we were at the briefing. Good. I wanted them to get as much rest as possible while they could. We'd had a lot of downtime on the Gettysburg, but resting on solid ground is different than on a spaceship. Between the variable gravity, the acceleration/deceleration periods, and very cramped quarters, rest on a ship was never very restful, at least it never was for me.

No one was still asleep when the mess hall opened though. Since it wasn't a combat landing we didn't have to do the intravenous feeding before, but they still didn't give us breakfast before we embarked, so it had been almost 24 hours since we'd eaten. Except what we'd stashed, of course. They didn't feed us, but we weren't under orders to avoid eating as we would be before a drop. And marines always have food stashed someplace. I'd eaten a couple energy bars I had stashed, and most of the troops were significantly better scroungers than I was.

The Emperor's Fist

The Emperor's Fist Blood on the Stars Collection 1

Blood on the Stars Collection 1 Attack Plan Alpha (Blood on the Stars Book 16)

Attack Plan Alpha (Blood on the Stars Book 16) BOB's Bar (Tales From The Multiverse Book 2)

BOB's Bar (Tales From The Multiverse Book 2) The Others

The Others Nightfall

Nightfall Empire's Ashes (Blood on the Stars Book 15)

Empire's Ashes (Blood on the Stars Book 15) Wings of Pegasus

Wings of Pegasus Crusade of Vengeance

Crusade of Vengeance The Last Stand

The Last Stand Blackhawk: Far Stars Legends I

Blackhawk: Far Stars Legends I Call to Arms: Blood on the Stars II

Call to Arms: Blood on the Stars II Cauldron of Fire (Blood on the Stars Book 5)

Cauldron of Fire (Blood on the Stars Book 5) Revenge of the Ancients: Crimson Worlds Refugees III

Revenge of the Ancients: Crimson Worlds Refugees III Crimson Worlds Successors: The Complete Trilogy

Crimson Worlds Successors: The Complete Trilogy The Grand Alliance

The Grand Alliance Portal Wars 1: Gehenna Dawn

Portal Wars 1: Gehenna Dawn MERCS: Crimson Worlds Successors

MERCS: Crimson Worlds Successors Crimson Worlds: 08 - Even Legends Die

Crimson Worlds: 08 - Even Legends Die Winds of Vengeance

Winds of Vengeance Invasion (Blood on the Stars Book 9)

Invasion (Blood on the Stars Book 9) A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds III)

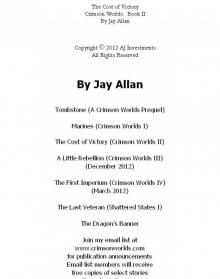

A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds III) Marines

Marines Black Dawn (Blood on the Stars Book 8)

Black Dawn (Blood on the Stars Book 8) Shadow of Empire

Shadow of Empire Galactic Frontiers: A Collection of Space Opera and Military Science Fiction Stories

Galactic Frontiers: A Collection of Space Opera and Military Science Fiction Stories Winds of Vengeance (Crimson Worlds Refugees Book 4)

Winds of Vengeance (Crimson Worlds Refugees Book 4) Dauntless (Blood on the Stars Book 6)

Dauntless (Blood on the Stars Book 6) Portal Wars: The Trilogy

Portal Wars: The Trilogy Marines cw-1

Marines cw-1 The Cost of Victory

The Cost of Victory Marines (Crimson Worlds)

Marines (Crimson Worlds) The Ten Thousand: Portal Wars II

The Ten Thousand: Portal Wars II The White Fleet (Blood on the Stars Book 7)

The White Fleet (Blood on the Stars Book 7) Crimson Worlds Collection III

Crimson Worlds Collection III The Black Flag (Crimson Worlds Successors Book 3)

The Black Flag (Crimson Worlds Successors Book 3) Tombstone

Tombstone Gehenna Dawn

Gehenna Dawn A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds)

A Little Rebellion (Crimson Worlds) Ruins of Empire: Blood on the Stars III

Ruins of Empire: Blood on the Stars III Dauntless

Dauntless Shadows of the Gods: Crimson Worlds Refugees II

Shadows of the Gods: Crimson Worlds Refugees II The Dragon's Banner

The Dragon's Banner Echoes of Glory (Blood on the Stars Book 4)

Echoes of Glory (Blood on the Stars Book 4) Crimson Worlds: 04 - The First Imperium

Crimson Worlds: 04 - The First Imperium The Prisoner of Eldaron: Crimson Worlds Successors II

The Prisoner of Eldaron: Crimson Worlds Successors II The Cost of Victory (Crimson Worlds)

The Cost of Victory (Crimson Worlds) Duel in the Dark: Blood on the Stars I

Duel in the Dark: Blood on the Stars I Into the Darkness: Crimson Worlds Refugees I

Into the Darkness: Crimson Worlds Refugees I Crimson Worlds Refugees: The First Trilogy

Crimson Worlds Refugees: The First Trilogy The Cost of Victory cw-2

The Cost of Victory cw-2 Stars & Empire 2: 10 More Galactic Tales (Stars & Empire Box Set Collection)

Stars & Empire 2: 10 More Galactic Tales (Stars & Empire Box Set Collection) Flames of Rebellion

Flames of Rebellion Stars & Empire: 10 Galactic Tales

Stars & Empire: 10 Galactic Tales The First Imperium cw-4

The First Imperium cw-4 Crimson Worlds: 07 - The Shadow Legions

Crimson Worlds: 07 - The Shadow Legions Storm of Vengeance

Storm of Vengeance Crimson Worlds Collection I

Crimson Worlds Collection I Rebellion's Fury

Rebellion's Fury Homefront: Portal Wars III

Homefront: Portal Wars III Tombstone (crimson worlds)

Tombstone (crimson worlds) Crimson Worlds: Prequel - Bitter Glory

Crimson Worlds: Prequel - Bitter Glory Crimson Worlds: Prequel - The Gates of Hell

Crimson Worlds: Prequel - The Gates of Hell The Fall: Crimson Worlds IX

The Fall: Crimson Worlds IX Crimson Worlds: War Stories: 3 Crimson Worlds Prequel Novellas

Crimson Worlds: War Stories: 3 Crimson Worlds Prequel Novellas Enemy in the Dark

Enemy in the Dark Crimson Worlds Collection II

Crimson Worlds Collection II